On ‘Counter-Plan’ and socialist planning: An interview with Mesut Odman

Translated: Etkin Bilen

In this issue of the journal, we interviewed Mesut Odman, one of the important intellectuals of the socialist movement in Turkey. Odman, who is experienced in socialist economy and planning, takes part in the group preparing the "counter-plan" of the Workers' Party of Turkey (TİP) as an answer to the five-year development plan of Turkey's State Planning Agency (DPT) in 1977. The interview sheds light on the relation of the socialist movement in Turkey during its rise with Marxism and the ruptures within the movement as a result of this experience. Mesut Odman makes enlightening comments for the young scientists regarding the position of Engels in Marxism, which is also the main topic of this issue of our journal.

Who is Mesut Odman?

He studied economy and statistics at the Middle East Technical University (METU) from 1967 to 1972. He worked at the Ministry of Labour for two years, followed by a position at the National Productivity Centre (MPM). He conducted and directed researches on economic and social problems. He held classes at METU (ODTÜ) and the Public Administration Institute for Turkey and Middle East, retiring in 2000. He wrote regular columns for socialist periodicals Yürüyüş, Yurt ve Dünya, Sosyalist İktidar (1979-1980), Toplumsal Kurtuluş, Hepileri, Komünist, Gelenek and soL. In addition to some writings regarding his profession, he is the author of Her Zaman Sosyalizm (2000 - a collection of his column writings), and two poetry books: Sessiz Yürüyüş (1995) and Geceyi Bölen Şiirler (2000). He also translated Reader in Marxist Philosophy: From the Writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin (ed. Selsam H., Martel H., 1963) to Turkish. He contributed to scientific works as a member of the Left Assembly (soL Meclis) and the Assembly of Socialists (Sosyalistlerin Meclisi). He still writes regular columns for soL Haber.

Can you talk a little bit about yourself? How did you get familiarised with socialist ideas?

Where shall I start? I was the child of a laborer family. My father was a forester, a civil employer, born in Gürün district of Sivas. My mother was a housewife, whose father was a Bulgarian migrant from Ruse, a teacher. I started primary school at a village school, giving education in a composite classroom of the first five grades. I completed my primary, secondary, and high school education in Gelibolu, Çanakkale and Bursa provinces. I started METU in 1967, but I got familiarised with left wing ideas in Çanakkale, not at METU.

We were interested in theatre while I was in the final grade of secondary school. Theatre was popular among the university students. Üstün Korugan, a brother, who was studying medicine, used to give us drama trainings during summer holidays. There was a theatre club in mid-60s called Youth Theatre and supported by the municipality. No wonder why it was called ‘the glorious 60s’! Çanakkale was a small town at those days, with a population of 19,500. I vividly remember this because it was written on the sign at the city entrance. I got the idea that being a leftist was a good thing from that brother of ours. I started reading Yön journal of Doğan Avcıoğlu. It was a weekly journal and I was an ardent reader of it, carrying in my schoolbag when I was a high school boy. It was also influential for me. But I became a communist at METU and among the circles of the Workers' Party of Turkey (TİP). That's why I name 1967 as the date when I became part of the organised socialist movement.

How did you become a communist at METU?

I became a member of the METU Socialist Thought Club (SFK) and held an executive role in a couple of months. We used to be dormitory mates with Sinan Cemgil [a prominent youth leader later killed during guerrilla warfare], who advised me to the executive board. I became a member of the TİP then, again with the reference of Sinan. Almost all of us were members of the TİP back then. However, there was a sudden and sharp change, as I wittily tell my young comrades: We slept as young members of TİP and woke up as democratic revolutionaries on the other day! The transformation was that sudden... However, I remained a socialist revolutionary, and a few people including me became the singular examples of those insisting to remain in TİP.

Staying on the socialist revolutionary road is strongly related with Marxist basis. Did the acquaintance with Marxism developed parallel to the process of leftism and communism?

When the TİP members were elected as parliamentary members in 1965, I was following them. Yön journal used to be available in Bursa, but I don't remember a publication of the party, being regularly available. I was an ardent reader during my last year in high school. There were children in the same school, who were sons of members of the Teachers' Union, they were not reading much, but some of them used to borrow books from me. When I started university in 1967, the number of publications increased. Sol Publishing was found in Ankara, and Doğan Avcıoğlu also established a publishing house. According to what some said, Doğan Avcıoğlu founded that publishing house just to publish books of Nazım Hikmet. Nazım Hikmet’s influence as a poet on the socialist and Marxist development of the youth is an exceptional example. Avcıoğlu published a part of Nazım's Human Landscapes from my Country with the title of "The Epic of Turkish Independence War". I used to carry it in my bag too, partly to show off and to arouse curiosity. Such things were most probably common in other parts of our country back then.

So, Marxism got into your life from a more cultural channel...

I need to emphasize the working class origins of my family as well. I was fond of reading too, carrying two suitcases during my holidays. One was full of books. My friendship with Sinan Cemgil developed also by means of curiosity about reading. He was a student in the department of architecture, dealing with projects in the studio at nights. He used to find me reading books when he turned back to the dormitory. I remember him saying "So, you are reading Marx, fine, but it doesn't make sense without becoming a member of the party." And there was such a contradictory situation: The means for reading was limited. Marxist classics were recently being translated into Turkish. We had limited opportunities to get those publications. It increased only by the end of the 60s. Our chances to get them in other languages were also increasing only by then.

Were the youth being educated about Marxism in the Workers' Party of Turkey?

I became a party member when I was eighteen because that was the minimum age required. Naturally you would expect that the party provided me with a Marxist background, but teaching and encouragement within the party was insufficient. For example, Mehmet Ali Aybar [the party leader, an athlete by profession] commenced on a polemic with the Communist Manifesto by arguing that "the history of the all existing society is the history of the struggle for freedom", which was opposed by Behice Boran [the succeeding leader of the party, a scholar in sociology]. Marxist classics were popular especially among the university students since they were just being translated. Leftist students were eager to learn Marx, Engels and Lenin. Aybar had some objections like "let's not direct them so that they do not have one-sided thought", as far as what we heard. Although Marxist classics were being read, the youth of the Workers' Party of Turkey was slower than the youth among the national democratic revolutionaries. The latter used to adhere to Lenin in their idea of "the primacy of a democratic revolution".

Was there any change in Workers' Party of Turkey during the period of Behice Boran?

I cannot say there was a systematic education in the second period of TİP [1976-1980]. Yalçın Küçük [a prominent socialist economist and intellectual] said "The first TİP [1961-1971] was a lot more influential and important in our political history, but the second TİP held Marxism in a more serious way, although it was a less influential party." I agree with this idea. In an article on the history of the party published in the party's biweekly journal, Çark Başak, Behice Boran said the first TİP "evolved and developed in the way of scientific socialism" and the second party was found within this direction. And yet, I cannot say that education within the party was taken seriously. During the second TİP, a publication house called Bilim Yayınları was found under the supervision of the party. They published recent Marxist books rather than Marxist classics. Books on Latin America, the history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and current issues were published. Reader in Marxist Philosophy, which has been recently published by Yazılama publishing house, was first published by that publishing house in 1976 with my translation.

Recently one of the best-selling books published by Yazılama is the Communist Manifesto. Can we say that an interest towards communism is re-emerging?

I heard a similar thing about the Reader in Marxist Philosophy what you mentioned about Manifesto. D&R bookstore orders books as they run out of them, and the Reader is generally among them. It had its second edition in a short time. It is a complex and difficult book. This means that there is an interest following a waste and disadvantaged period. The dissolution of the USSR attracts an actual interest, but Marxist philosophy doesn't. Its original title is Reader in Marxist Philosophy, but we published it with the Turkish title of Kılavuz [guide]. Still, I don't personally believe that the interest in such texts can revive as it were in the 60s and 70s. And yet, there is a certain new interest.

If there is such a parameter, what kind of guidance is needed?

What can be done as a political organization? The question needs to be put this way. The people need to be guided. The classics are there for more than a century. It is a famous saying by Marx that one needs to be a bookworm. Marx's life, however, was spent in struggle, being exiled from country to country. All his writings are polemics with the people and political ideas he was struggling against. That is why something needs to be done to ease reading these books after 150 years. Anti-Dühring mentions a whole lot of names starting from its title. Especially in their books regarding class struggles directly, for example The Class Struggles in France and Civil War in France, current issues are mentioned, making reading process more difficult. While publishing these books, one has to add a historical summary, present the political regime back then, include important political events, which altogether corresponds to quite a daring political and ideological mission. These would increase reading. The reader needs such a help, I think, so that they can read and understand these books on their own. In addition to this, these books need to be integrated into the education within the party. It will be a lot better if they are supported by fiction reading as well.

The title of this issue of our journal is “Engels and Science”. Can you comment, first of all, on the ideas that consider Engels' position within Marxism as being a reductionist, which posits a discrepancy between Marx and Engels?

Aligning Lenin and Engels on one side and putting a discrepancy between Marx and them is an approach that started last century. We can say such distortions decreased as interest in Marxism diminished compared to the period when the Reader was published. Aside from those who speak ignorantly, it is absurd that knowledgeable enemies can argue such things. It is impossible if one knows the nature of personal and comradely relation between these two men. Marx and Engels are always in collaboration. Manifesto is among their early works of their youth. The film entitled Young Karl Marx, which also gives the writing process of that work, is a successful and honest movie. One would never find a better story if she wanted to write a story about the friendship of two people.

One of the most important scientific works of Engels is the Dialectics of Nature, for which he started to take notes in his 50s. His study terminates in 1883, following Marx's death. How can you describe the place of science in Engels' life?

When Engels first started to consider writing the Dialectics of Nature, the work which caused the argument of reductionism most as far as I know, he was in contact with Marx. Marx deals with mathematics, the history of technology and agricultural chemistry before starting to write the Capital. He also reads chemistry, biology, geology, anatomy and physiology. Engels, on the other hand, deals with physics and biology, in addition to mathematics, astronomy, chemistry and physiology and studies theoretical natural science. Some biographies write that he studied these at the university, but it should not be misunderstood. What he did was to attend conferences and discussions, correspond with scientists and read on these topics. Marx encourages him when he starts writing the Dialectics of Nature. He continues until Marx's death in 1883. He starts writing the Anti-Dühring at intervals, leaving the Dialectics of Nature aside for a while. They decide on that work together. They agree that they need to organise scientific socialism as a whole, given that 30 years had passed since they started discussing and writing on it. Engels takes on the responsibility. They call the Anti-Dühringas an "Encyclopaedia of Marxism". Engels explains his aim of writing the Dialectics of Nature in his preface to the second edition of the Anti-Dühring. He says “It goes without saying that my recapitulation of mathematics and the natural sciences was undertaken in order to convince myself also in detail – of what in general I was not in doubt – that in nature, amid the welter of innumerable changes, the same dialectical laws of motion force their way through as those which in history govern the apparent fortuitousness of events. And finally, to me, there could be no question of building the laws of dialectics into nature, but of discovering them in it and evolving them from it.”

What kind of a relation do they formulate between science and politics?

All kinds of scientific and philosophical writing of both are directly connected to political struggle. Eugen Dühring was a well-acclaimed professor with numerous followers, and Marx feels the need “to stop this”. The necessities of actual political struggle impose such a need. Engels suspends his studies on science and starts working on the Anti-Dühring. In the Dialectics of Nature, he works on several scientific fields from astronomy to biology and physics, reading extensively as the professional writers of those fields. However, he cannot finish it, dealing with the Anti-Dühring at intervals. Lenin cannot see the publication of that work. If Lenin had seen what Engels had written while writing Materialism and Empirio-criticism, he would had included other discussions. The Dialectics of Nature was first published in 1925 in the USSR. I took a look at his article "The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man" recently while I was writing my column in soL regarding Kaz mountains [the gold mining project in Mount Ida]. When I read what Engels wrote on these issues, I felt like saying "you, environmentalists, just read what Engels wrote, you will learn a lot."

Professor Gamze Yücesan-Özdemir published an impressive article in soL news portal on August 5 for the anniversary of Engels' death. She opened a discussion on the disregard of Engels in Marxism by the post-Marxists and left-liberals. To what extent is Engels given credit within Marxism in its totality?

Gamze’s article was really good. I also dwelt on the issue of creating a disparity between Engels and Marx in my article on the Anti-Dühring in the journal Komünist in December 2012. We can also give an example from the dissolution of the Soviet Union. We know that Engels' book was first published in 1878. In 1988, when Gorbachev was the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the 110th anniversary of the Anti-Dühring's publication was celebrated in a round table meeting that gathered scientists from different fields, predominated by the economists. It is as if they celebrate the anniversary of the book as a screen to camouflage themselves by saying “the 110th year of the memorable book by the great thinker Engels”. They almost curse it in an instant, saying such words like “Of course we cannot expect Marx and Engels to guide us by rising from their graves”, or “If we are to deal with economics, we need to dwell on the mutual aspects of the capitalist and socialist systems and how they can be solved simultaneously.” They ultimately note the need to discard the Anti-Dühring altogether. Just within three years, it was them who were discarded by socialism or the history itself, as we know very well.

The Dialectics of Nature also aimed to challenge the idealist perception of the relation between man and nature. One of the approaches that naturalize capitalism today is the ahistorical idea of those materialists disregarding the 6th thesis. Such ideas are not original to the present day, are they?

I happened to see Özdemir İnce's column today [18th August] in Cumhuriyet newspaper. We can perceive it as an example of diverging from the classics of socialism, and thus from its core in a different country. İnce talks about a conference of writers he participated in Bulgaria in 1983. A poet, who is also the assistant of the president in cultural affairs, says to İnce, “I believe what Marx, Engels and Lenin posited in their analyses were wrong. (...) The human nature approximates to capitalism rather than to collective property and socialism. Capitalism needs to exhaust its own life, and people need to excel by getting rid of their selfishness so that they can maintain socialist ideas.” We can detect two erroneous ideas here. Firstly, anyone who is knowledgeable a little bit about in what Marx and Engels wrote knows that they emphasised the faultiness of talking about a “human nature” devoid of historical and social context. Secondly, a world in which people get rid of their selfishness by the self-exhaustion of capitalism did not exist in the minds of the founders of the socialism nor can it ever exist in actuality.

It is known that Marx and Engels did not write much about planning and the foundation of socialism. And yet, the Anti-Dühring provides a general outline congruous with the program of socialism. There are some points like the nationalisation of the private property by the proletariat, thus heading towards classless society and like overcoming the anarchy of production by planning.

Both Marx and Engels wrote little about the foundation of socialism. Their most important political opponents back then were the utopian socialists. We translate utopia as a "non-existent society", providing imaginations on production, distribution, education and the like. Marx and Engels criticise such ideas because they both need to oppose it politically and theoretically, saying that theirs is a scientific view. In his ‘Preface’ to the A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx says "mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve." This is one of the ideas at the core of the historical materialism and they are correct given the conditions of their times. I mention "the conditions of their times" because we now know a period that took almost a century which witnessed the foundation of socialism, or let’s say the assertion to establish it across nearly one third of the world and its downfall after the dissolution. That experience will guide us, and we will analyse it, writing on the foundation of socialism, for sure. One of the few books, which seems a little bit incongruous with this argument in the ‘Preface’ is the Anti-Dühring. In the chapter ‘Socialism’ of Anti-Dühring, Engels writes on economic and social issues to an extent that has never been done either by Marx or himself. This third chapter of the Anti-Dühring will be an important resource for us when we seize power. There is a sentence in that book which says "The proletariat seizes political power and turns the means of production in the first instance into state property." He means that it will first be the state property, evolving to social and more advanced property types. This is important.

Why is it important?

The argument of all the revisionists saying, “capitalism and socialism approximate to each other"”, which is the “convergence theory”, is actually a theory of the bourgeoisie and yet it found proponents in real socialism. Such ideas need to be challenged strongly. Why? Because it opens the way to retreat from socialist power! They argue that political power is the source of all kinds of trouble. That is why, from their standpoint, talking about the political power of the working class means moving away from Marxism. But how come this can be true, given that they already wrote about it in the Manifesto! In the Anti-Dühring, there are some conclusions that will undo the ideas of the ones who want to reconcile socialism and capitalism. That is why their professional representatives especially during the last period of the Soviet Union try to discard this work at its 110th publication anniversary. What I mean is that, this book has been subject to the attacks of the enemies of socialism from the start. The Anti-Dühring is a book that must be read and understood by the young people. Especially the chapter on socialism.

The scientific implementation of Marxism is possible only by means of getting organised. One of your most valuable experiences in this sense is the preparation of the "Counter-plan" of the Workers' Party of Turkey in 1977. You presented it in the symposium “Which Resources Will Socialist Turkey be Built on?” held in 2003. The deviation towards democratisation in the struggle for socialism that you witnessed in your youth appears once again during the publication of the Plan. Can you tell us about it?

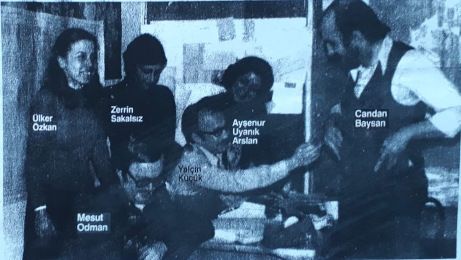

There was a Bureau of Science and Research under the executive committee of TİP. The work was conducted under the responsibility of the bureau. A worker comrade from Zonguldak, Yavuz Ünal, was the secretary of the bureau. We became members of the bureau just before the work started. Yalçın Küçük, Candan Baysan and me. Yalçın Küçük was the editor in chief of the Yürüyüş journal, a very influential weekly publication of the party. He was a close friend of Behice Boran. Candan and I were actually responsible from the whole work. We were responsible from gathering all those people working in the study from or outside the ranks of the party, guiding them and acting in a way as the political commissars in the meetings of the study group. Here is a photograph from those days. It was taken in the room devoted to us at the office of the Yürüyüş journal in Konur street in Ankara. Deniz Hakan printed this photo given by Yalçın Küçük in Aydınlık newspaper when he used to write a column there. This is the only photograph of the place where we worked.

We mentioned the importance of reading fiction in terms of learning Marxism. The issue of arts was also discussed in relation to the reasons why the second Workers' Party of Turkey could not embrace the plan you prepared and changed it.

The core of the plan included physical proportions, analysis of the real condition, five year plans and projections, and the final part included sectoral analysis. This also included arts and culture. If we are to use the same terminology, this "sector" was also under my responsibility. We got the contributions of very important artists. We used to gather in Ankara. Figures like Demirtaş Ceyhun and Kemal Özer who used to live in İstanbul were staying in our homes. Adalet Ağaoğlu, who was living in Ankara, participated in our gatherings too. I do not remember exactly how much Sevgi Soysal participated in our gatherings. She was struggling with cancer, but she must have participated as much as she could because she was such a militant person. Yılmaz Onay, who passed away a couple of years ago, also used to be there. We considered Adalet Ağaoğlu, Demirtaş Ceyhun, Kemal Özer and Yılmaz Onay as our elders. We were young, but they worked with us in harmony, showing discipline. However, the final version of the plan did not include this section on arts. We had no idea why it was removed. I remember saying in that symposium in 2003 that those who removed it might have thought "how ever can you plan arts".

You also talked about a distortion regarding tourism in your presentation in the symposium.

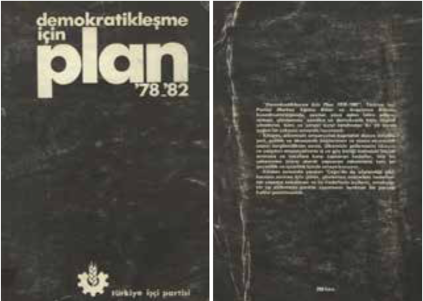

Yes, we excluded the word “tourism” as a sector in the plan and talked about the “holiday of the workers”. We explained that it is conventionally considered as a sector in the bourgeois plans, but the important thing in our struggle is the holiday and resting period of the toiling masses. It is of course important in terms of the international brotherhood that the workers of other countries come to our country, but we cannot see it as a source of foreign currency. We took the foreign currency from international travel at minimum while calculating the balances in other parts of the plan. We substitute it with other resources in our approach. The holiday of the working class was a socialist concept and yet they changed it into “tourism for the holiday opportunity of the employees” while redacting the text. We had totally erased the concept of tourism, though. The plan was finally published with these changes under the title 78-82 Plan for Democratisation. That was not our title. They changed the title because “National democratic front” policies were being adopted among the party centre by that time. The socialist revolutionary plan of ours was challenging those ideas. Let's say that they preferred to publish the plan that would be quite prestigious against the plan of the bourgeoisie, after making such changes.

What would be the title of your plan?

It was not settled as yet by then. However, we used to mention as the “Counter-plan” in our daily talk. There was not a definite decision. We were saying that we would perfectly implement that program if we were to seize power, let's say in 1977. We had never argued that we would establish a socialist economy gradually in two, three or five years. Our perception was that we would have set the main foundations of a socialist economy during the five-year plan period after we seized power, by setting goals and showing ways of reaching those goals. We were not arguing that we would open a way to democratisation with this plan; on the contrary, we were saying that we would open a way to socialism. The party did not object to this perspective initially. However, the work was later taken away. Finally, Candan and I resigned by sending a letter to the bureau and Yalçın Küçük, who was in charge of the work.

What were your objections to the title “Plan for democratisation”?

We argued that plans are made for industrialisation, not for democratisation. And industrialisation is a means to set the foundations of socialism. Let me refer to one of rare documents as an example of our main objections. We said these things: With an analogy to the famous saying of those days "we need bread, not a plan" [an expression of the right-wing Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel], saying plan for democratisation instead of for socialism means saying “we need democracy rather than socialism”. This is quite in congruity with the changes done during the publication phase of the plan. Arguing for bread instead of a plan does not only mean promoting consumption instead of production, it also means giving priority to agriculture and services sector (trade, rent and profit) instead of industry, considering the three main sectors of the economy. Emphasising democracy instead of socialism also means "being obsessed with democracy" as we used to call it those days. There are some lessons we can gain from this experience. The ones who are interested can take a look at the results section of the symposium proceedings of “Which Resources Will Socialist Turkey be Built on?”.

You talk about some constraints of working on a similar Counter-plan in your work in 2003. An interview with you regarding this issue was published 10 years later during the June Resistance of 2013 in Turkey. There you say “In my opinion, it is better to talk about what will be done starting from the very first day of socialism and the works that will follow from there in the long run rather than talking about 5 year plans.” Nowadays, the Science and Enlightenment Academy (BAA) is preparing a symposium on Socialist Future and Planning, aiming to gather a series of scientific reports ranging from short and long term plans. It partly aims to revive the issue of planning and partly to show no long term plan can be implemented without taking revolutionary steps.

Is it possible to remake such a study in concrete terms? Can we accomplish a similar work given the conditions of today? You need to define the existing conditions, main sectors, the handicaps, the rise in population, how much food will be needed and the figures on machinery and equipment. While the counter-plan was being prepared, Behice Boran had an influence on the leftists as a militant academic. Yalçın Küçük had the prestige as one of the persons who had already prepared the first plan of Turkey [the first official Five-Year Development Plan (1963-67)]. People who were influenced by them were employees in the State Planning Agency (DPT). We are talking about people who devote their time after the work without looking for any personal interest. Even Bilsay Kuruç, the undersecretary of the State Planning Agency! He did not personally participate in the counter-plan studies but was aware of them; if it was not for him, we could have used neither the resources nor the personnel of the agency. We do not have such advantages today. The State Planning Agency itself that existed in 2003 has now disappeared! That is why it is impossible to do the same work. It is not necessary either.

Then, what is necessary?

We need to do something different but in what sense? There is a concept like “guerrilla planning” in the communistic planning literature. It can be summarised as making a plan by considering the immediate problems and finding the most exact solution in the shortest time rather than calculating balances by means of five-year and single-year figures. This approach can be dwelt on. We can do it without having our own specialists among the state agency providing us the necessary data. We can try to take some economic and, more than that, political decisions by considering what can be the first five main problems starting from the very first day of our power and how we can solve them by looking at the more general data. The political results of such an approach can be more concrete.

Of course we need some qualified people to do this. However, a study can be conducted by a group of people who follow the Turkish economy and are aware of its problems and who are politically mature. I believe this can work. There can be some issues that are not directly related to planning, and that is why the symposium talks about “socialist future”. We can discuss with the contributors of the symposium on the question of what can be done in the very first day of our rule, or as the bourgeois politicians sometimes call “in the first 100 days”, to overcome the biggest problems and gain the support of the people. Such contributions will be politically influential as well.

Thank you.

It was a pleasure for me.